ABSTRACT: A retrospective analysis of healthcare-associated infections was conducted among patients admitted to a 12-bed paediatric intensive care unit in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, from January 2019 to December 2023. No significant changes to healthcare-associated infection rates or length of stay were observed among patients admitted during the pre-pandemic, pandemic, or post-pandemic periods.

Meghan Engbretson, MSc1*, Joshua K Schaffzin, MD2,3, Dayre McNally, MD2, 3, George Gubb, RN1, and Nisha Thampi, MD1, 2, 3

1 Infection Prevention and Control Program, Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

2 Department of Pediatrics, Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

3 University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

*Corresponding author

Meghan Engbretson

Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario

Ottawa, Ontario

Canada

Article history:

Received 20 June 2025

Received in revised form 6 October 2025

Accepted 16 October 2025

ABSTRACT

A retrospective analysis of healthcare-associated infections was conducted among patients admitted to a 12-bed paediatric intensive care unit in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, from January 2019 to December 2023. No significant changes to healthcare-associated infection rates or length of stay were observed among patients admitted during the pre-pandemic, pandemic, or post-pandemic periods.

INTRODUCTION

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic posed significant challenges to healthcare systems in both adult and paediatric populations. Increased rates of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) in hospitalized adults during this time have been described, and have been correlated with overcrowding of adult intensive care units treating SARS-CoV-2 patients, healthcare worker redeployments, and staff fatigue. The effects of personal protective equipment shortages have also been described in adult hospital settings (Blot et al., 2022; Weiner-Lastinger et al., 2022). Though increases in healthcare-associated SARS-CoV-2 infections were observed in later waves of the pandemic (Lee et al., 2024), the pandemic’s impact on other HAI rates remains underreported, especially in the post-pandemic period. Factors contributing to overall HAI rates in the paediatric population, including staffing ratios, invasive device use, and length of stay, are not well-described in this group. This study aimed to identify trends in HAI rates, including the burden of HAI by type, across pre-pandemic, pandemic, and post-pandemic periods.

METHODS

This retrospective study included all paediatric patients under 18 years of age admitted to the 12-bed paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO) in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, between January 2019 and December 2023. Patients were grouped by pre-pandemic (January 1, 2019 to February 29, 2020), pandemic (March 1, 2020 to February 28, 2022), or post-pandemic (March 1, 2022 to December 31, 2023) time periods based on their date of infection. Patients admitted to the PICU for 48 hours or longer were included, as infections in shorter admissions could be attributed to the referring location or the community. Routine review of each potential HAI was conducted by the infection prevention and control (IPAC) team as part of the surveillance program and, therefore, research ethics board approval was not required. Central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs), healthcare-associated viral respiratory infections (HAVRIs), catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs), and infections with antimicrobial-resistant organisms (AROs), including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, carbapenemase-producing organisms, vancomycin-resistant enterococci, and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing organisms, as well as Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI), were included. CLABSIs, HAVRIs, CDI, and infections with AROs were classified based on definitions provided by the Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program (CNISP, 2024). HAVRI detection methods were unchanged during this study period: all ICU patients with new respiratory symptoms identified after three days of hospitalization were tested for adenovirus, influenza A and B, parainfluenza (types 1, 2, 3, and 4), rhinovirus, bocavirus, non-SARS coronaviruses (229E, NL63, and OC43), enterovirus, human metapneumovirus, and respiratory syncytial virus by multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Testing for SARS-CoV-2 was added in March 2020. All patients admitted to CHEO were screened for AROs based on risk factors, including community exposure, admitting service, previous healthcare experiences, and clinical indication. CAUTIs were evaluated using definitions from the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN Patient Safety Component Manual, 2024). HAI incidence rates (per 1,000 patient days) and device-specific infection incidence rates (per 1,000 device utilization days) were calculated for each period. Differences between groups were assessed using Kruskal-Wallis and pairwise Mann-Whitney U tests in Microsoft Excel, given the non-normal distributions and unequal sample sizes.

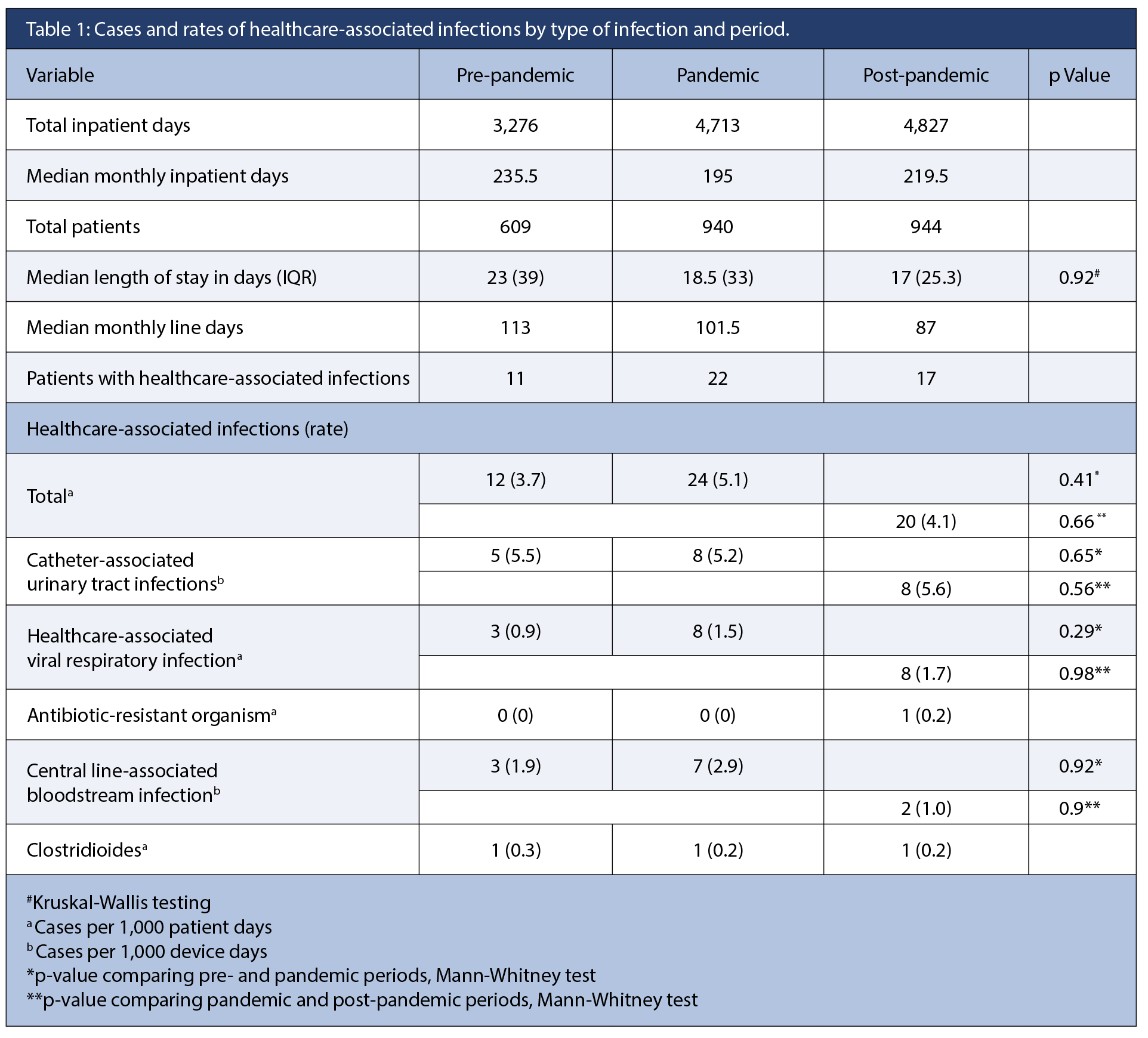

RESULTS

During the study period, 2,493 patients were included (Table 1). Among these, 50 patients had a total of 56 HAIs (4.4 cases per 1,000 patient-days) identified during their stay in the PICU. Patients with HAI had a mean age of 5.1 years (SD 9.6 years) and a range of one month to 16 years; 56% were female patients. Monthly patient days differed significantly across periods (H = 14.0, df = 2, p = 0.001), with higher values during the pandemic than pre-pandemic (U = 42, z = –3.8, p < 0.001). No other pairwise differences were significant after Bonferroni correction. Monthly line days also varied by period (H = 8.26, df = 2, N = 60, p = 0.016), driven by higher values during the pandemic compared with pre-pandemic (z = –2.76, p = 0.006).

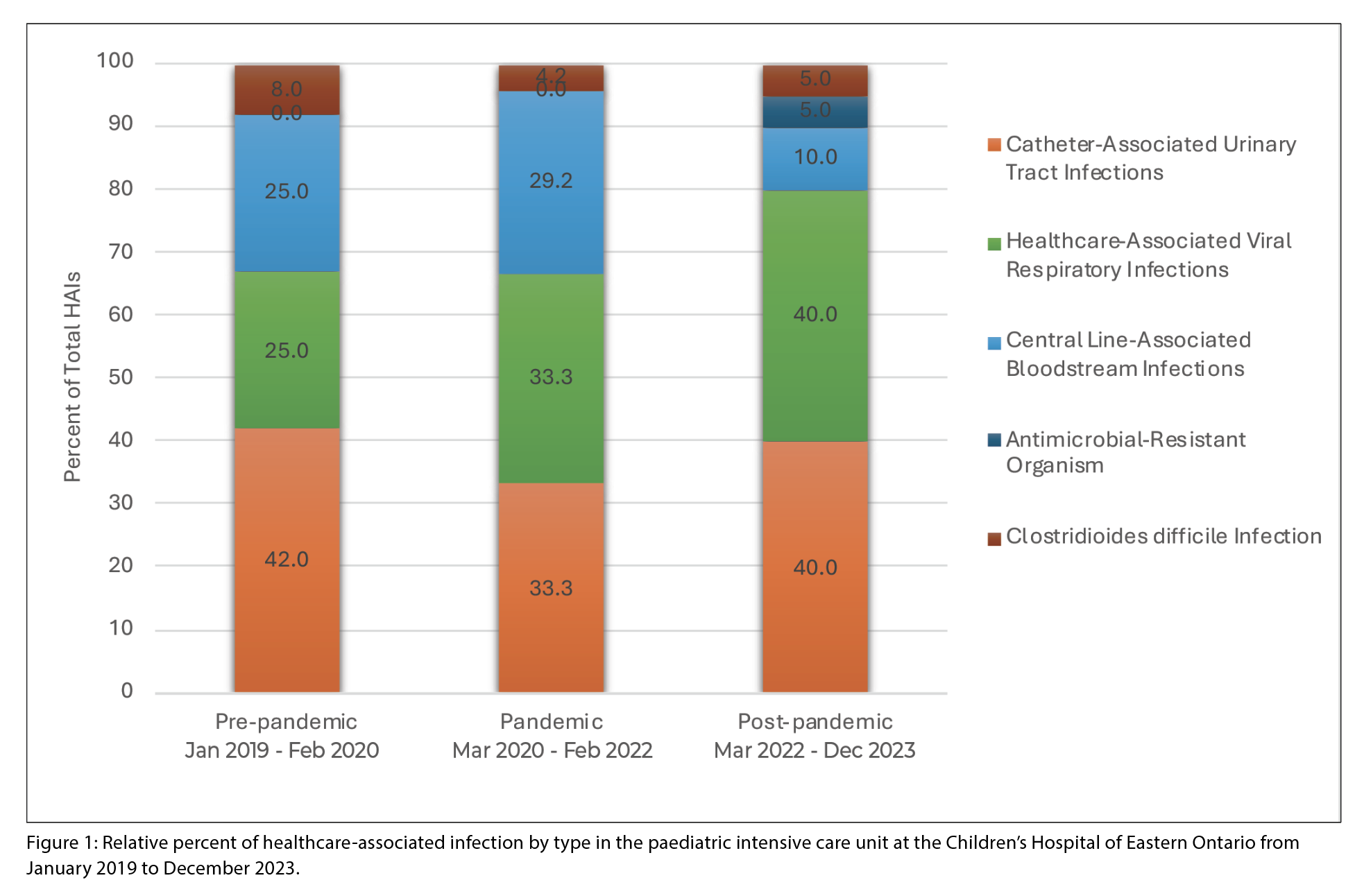

CAUTIs and HAVRIs accounted for the majority of HAI burden in the pre-pandemic period (37.5% and 34% of total HAIs identified, respectively), and this trend was sustained through pandemic and post-pandemic periods (Figure 1). The relative proportion of HAVRIs was higher in pandemic and post-pandemic periods, despite no changes in the detection methods. The proportion of CLABSIs decreased in the post-pandemic period compared with earlier periods.

DISCUSSION

The overall incidence rate for all HAI types across study periods was 4.4 per 1,000 patient-days, with the highest rate reported in the pandemic period (5.1 per 1,000 patient-days), although the difference in incidence rates between study periods was not significant. Paediatric HAI data specific to the critical care environment, apart from healthcare-associated SARS-CoV-2 infections, were not readily available in the literature at the time of review. Trends observed in data from adult or mixed centres in Canada were not extrapolated to this population because of the differences in care intensity and models of practice between adult and paediatric ICUs. One of the strengths of this study was the inclusion of data beyond the end of the pandemic, up to December 2023.

Throughout the study period, CAUTIs and HAVRIs represented the highest burden of paediatric HAIs in this single-site, tertiary care PICU in Canada. The relative burden of CLABSIs was incrementally higher (p = 0.62) in the pandemic period, but the changes across study periods were not significant. This increase reflects PICU data from Quebec, Canada, where a higher CLABSI rate was reported during the pandemic, along with increased catheter usage-to-patient-day ratio (Li et al. 2024).

The burden of HAVRIs compared to other HAIs was high across study periods, with higher proportions observed during the pandemic and post-pandemic periods compared to the pre-pandemic period. Increased HAVRI rates in the pandemic and post-pandemic period could reflect increased community incidence of viral respiratory illness, higher patient load within the PICU, or reduced adherence among healthcare workers and caregivers to routine infection control practices.

Unlike findings in prior studies showing decreasing length of stay in intensive care units during the pandemic period (Xia et al., 2022), we did not observe significant differences in length of stay among affected patients across study periods. This may reflect the small number of patients with HAIs included in the analyses, and therefore limited statistical power, as well as the absence of comparator data from patients unaffected by HAIs. We acknowledge this limitation of the study, as well as the limited liability to interpret these findings.

Understanding infection burden and trends can inform education efforts and control measures to reduce infection rates and allocate infection control resources more effectively within the PICU. Expanding this dataset to include other paediatric tertiary care facilities would allow further study of infection prevention strategies among critically ill children.

REFERENCES

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Healthcare Safety Network. (2024). Patient safety component manual [PDF]. U.S. Department of Health

and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn

Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program, & Public Health Agency of Canada. (2024). Healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial resistance in Canadian acute care hospitals, 2018–2022. Canada Communicable Disease Report, 50(5–6), 179–196.

https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/reports-publications/canada-communicable-disease-report-ccdr/2024-volume-50/issue-5-6-may-june-2024/healthcare-associated-infections-antimicrobial-resistance-canadian-acute-care-hospitals-2018-2022.html

Foster, J. R., & Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. (2022). Family presence in Canadian PICUs during the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed-methods environmental scan of policy and practice. CMAJ Open, 10(3), E622–E632.

https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20210209

Gibney, R. T. N., et al. (2022). COVID-19 pandemic:

The impact on Canada’s intensive care units.

FACETS, 7(1), 1411–1472.

https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2022-0023

Lee, D., et al. (2024). Trends in SARS-CoV-2-related

paediatric hospitalizations reported to the Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program, March 2020 to December 2022. Antimicrobial Stewardship & Healthcare Epidemiology, 4, e175.

https://doi.org/10.1017/ash.2024.175

Li, Y., et al. (2024). CLABSI rates variation prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic in two hospitals in Montreal, Canada. Canadian Journal of Infection Control, 39, [222-225].

Mitchell, R., Cayen, J., Thampi, N., et al. (2023). Trends in severe outcomes among adult and paediatric patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program, March 2020 to May 2022. JAMA Network Open, 6(5), e239050.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.9050

Paquette, M., Shephard, A., Bédard, P., & Thampi, N. (2022). Viral respiratory infections in hospitalized children with symptomatic caregivers. Hospital Pediatrics, 12(12),

e124–e128. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2021-006412

Xia, Y., et al. (2022). Mortality trends and length of stay among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Ontario and Québec (Canada): A population-based cohort study of the first three epidemic waves. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 121, 1–10.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2022.04.035