Background: Rotavirus is a commonly recognized cause of gastrointestinal illness in infants and young children. It is an underappreciated cause of gastroenteritis in adult patients. Clostridioides (formerly Clostridium) difficile is the most important infectious cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea worldwide. A mixed infection outbreak involving rotavirus and Clostridioides difficile has not been fully characterized.

Carmen Tse, MD1, Tonya Carson, BSc2, Ashley Shackleford, BSc, CIC², Erin Roberts, BScN, MBA, RN, CIC, CHE², Conar O’Neil, MD¹,², and Molly Lin, MD¹,²

1 Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

² Infection Prevention and Control, Covenant Health, Edmonton, AB, Canada

*Corresponding author

Carmen Tse

University of Alberta

Edmonton, AB, Canada

Email: ctse2@ualberta.ca

Phone: 204-799-1090

Article history:

Received 22 July 2025

Received in revised form 28 September 2025

Accepted 27 October 2025

ABSTRACT

Background: Rotavirus is a commonly recognized cause of gastrointestinal illness in infants and young children. It is an underappreciated cause of gastroenteritis in adult patients. Clostridioides (formerly Clostridium) difficile is the most important infectious cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea worldwide. A mixed infection outbreak involving rotavirus and Clostridioides difficile has not been fully characterized.

Methods: This report highlights a mixed outbreak of Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) and rotavirus among adult patients in a community hospital in Alberta, Canada, and describes the interventions implemented.

Results: On March 20, a CDI outbreak was declared following five cases of hospital-acquired CDI, and on March 25, one patient was identified with a co-infection. A mixed pathogen outbreak was then declared after three new cases of rotavirus were detected on the same unit. Infection prevention and control (IPAC) measures were implemented in accordance with local IPAC guidelines. In addition, hand hygiene, environmental cleaning, and fluorescent marker audits were conducted. A hand hygiene audit of 21 opportunities revealed 66.7% compliance. Fluorescent marker audits showed improper cleaning of patient environments and shared equipment. The ward received targeted education and enhanced cleaning based on audit findings. The rotavirus and CDI outbreaks were declared over on April 2 and April 10, respectively.

Conclusion: Considering that rotavirus is an underrecognized cause of gastrointestinal disease in adults, awareness of this pathogen as a potential cause of an outbreak is important to prompt early testing and ensure appropriate infection control interventions to prevent its spread.

KEYWORDS:

Clostridioides difficile, rotavirus, outbreak, healthcare-associated infections, infection prevention and control

INTRODUCTION

Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) represent a major challenge in acute care settings due to their high transmissibility and morbidity. Clostridioides (formerly Clostridium) difficile is the most important infectious cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea worldwide, and a leading cause of healthcare-associated infections, while rotavirus is an underappreciated but important cause of viral gastroenteritis in adult populations (Anderson & Weber, 2004; Finn et al., 2021). In Canada, rotavirus has been associated with approximately 7,500 hospitalizations annually, with an incidence of eight to 26 per 10,000 persons aged 18 and older, and an annual hospital costs of approximately CAD$3 million (Morton et al., 2015). The rate of hospital-acquired Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) ranges from 2.1 to 6.5 per 10,000 inpatient-days, with annual hospital cost of up to CAD$10 million (Choi et al., 2019; Xia et al., 2019).

CDI has well-established risk factors, including prior antibiotic use, advanced age, proton-pump-inhibitor use, and prior hospitalizations (Lourenço et al., 2025). It has a median incubation period of six days, and symptoms can include diarrhea, abdominal discomfort, fever, and severe complications such as septic shock, toxic megacolon and colonic perforation (Lourenço et al., 2025). C. difficile can form spores, which are resistant to oxygen, heat, acid, desiccation, and alcohol-based disinfectants, facilitating spread (A. N. Edwards et al., 2016). This resilience makes infection prevention and control (IPAC) measures, including the use of sporicidal cleaning agents, essential to prevent spread alongside appropriate treatment. Treatment includes antibiotics such as vancomycin, fidaxomicin as first-line therapy (Lourenço et al., 2025).

Rotavirus, in contrast, causes a self-limiting gastrointestinal illness and is transmitted primarily through direct person-to-person contact or via contaminated food and surfaces. While it can persist on surfaces for several days, it is generally susceptible to a variety of disinfectants and cleaning agents (Anderson & Weber, 2004; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2018). It has a median incubation period of two days (range: 1-3 days) (Lee et al., 2013). In children, it can cause fever, vomiting, and non-bloody diarrhea (Anderson & Weber, 2004). Adult infections are often underrecognized, with a clinical spectrum ranging from asymptomatic shedding to fever, malaise, headache, nausea, abdominal cramping, and diarrhea. (Anderson & Weber, 2004). Severe disease in adults is uncommon, but has been documented, including a rare case of hypovolemic or septic shock with multi-organ failure (N. Edwards et al., 2023).

Seasonality has been associated with rotavirus in children, with peak prevalence from February to March (Anderson et al., 2012; Wenman et al., 1979). During peak season, rotavirus was 2.4 times more common than all bacterial pathogens combined in a previous study completed in the United States (Anderson et al., 2012). It was also more common in those who were older and immunocompromised (Anderson et al., 2012; Morton et al., 2015). There is no specific treatment for rotavirus infection beyond supportive care, and no post-exposure prophylaxis is currently recommended. Therefore, to prevent spread of rotavirus, IPAC measures remain the most important intervention. To date, there have been no detailed outbreak reports on rotavirus in adults in Canadian literature, nor has there been any documents cases of mixed rotavirus and CDI outbreaks.

The current study describes the epidemiology, infection control response, and lessons learned from a mixed rotavirus and CDI outbreak that occurred between February 21 and April 10, 2025, in Alberta, Canada, with particular attention to IPAC interventions to control transmission.

METHODS

A retrospective observational outbreak investigation involving geriatric acute care medicine unit comprising 40 beds and 15 rooms in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. A case was defined as any patient admitted to the affected unit who developed laboratory-confirmed CDI or rotavirus infection during the period between February 21 and April 10, 2025.

Laboratory analysis

Microbiologic testing was performed on symptomatic patients presenting with diarrhea (three or more loose stools in 24 hours) using rapid membrane enzyme immunoassay (C. difficile Quik Chek Complete®) for the simultaneous detection of C. difficile common antigen (glutamate dehydrogenase antigen, GDH), and toxins A/B (Alberta Precision Laboratories | Lab Services, 2024). Specimens positive for only one of these targets (GDH-only or Toxin A/B-only) were tested by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Xpert® C. difficile/Epi) for confirmation. Non-diarrheal stool samples were rejected by the laboratory and were not processed. Rotavirus was also tested by PCR as part of a stool gastroenteritis viral panel (GVP). The GVP included norovirus, sapovirus, astrovirus, and adenovirus (Alberta Precision Laboratories | Lab Services, 2024). Data were extracted from electronic medical records, infection prevention and control (IPAC) surveillance logs, environmental audits, and hand hygiene audits.

Outbreak definitions

A gastrointestinal outbreak was defined as two or more hospital-acquired gastrointestinal (GI) cases with initial symptom onset within a 48-hour period and a common epidemiologic link (i.e., acquisition in the same room or from an individual in the workplace setting/facility (i.e., during their incubation period or period of communicability). Evidence of healthcare-associated transmission within the facility was also required (Alberta Health Services, 2024).

A CDI outbreak was defined as three or more cases present on a unit within a seven-day period, with a common epidemiological link.

A mixed pathogen outbreak was defined when pathogen-specific outbreak definitions were met for each of the pathogens (Alberta Health Services, 2024).

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of Alberta Health Research Ethics Board (HREB; Protocol #27155, REB# Pro00153067).

RESULTS

Descriptive epidemiology

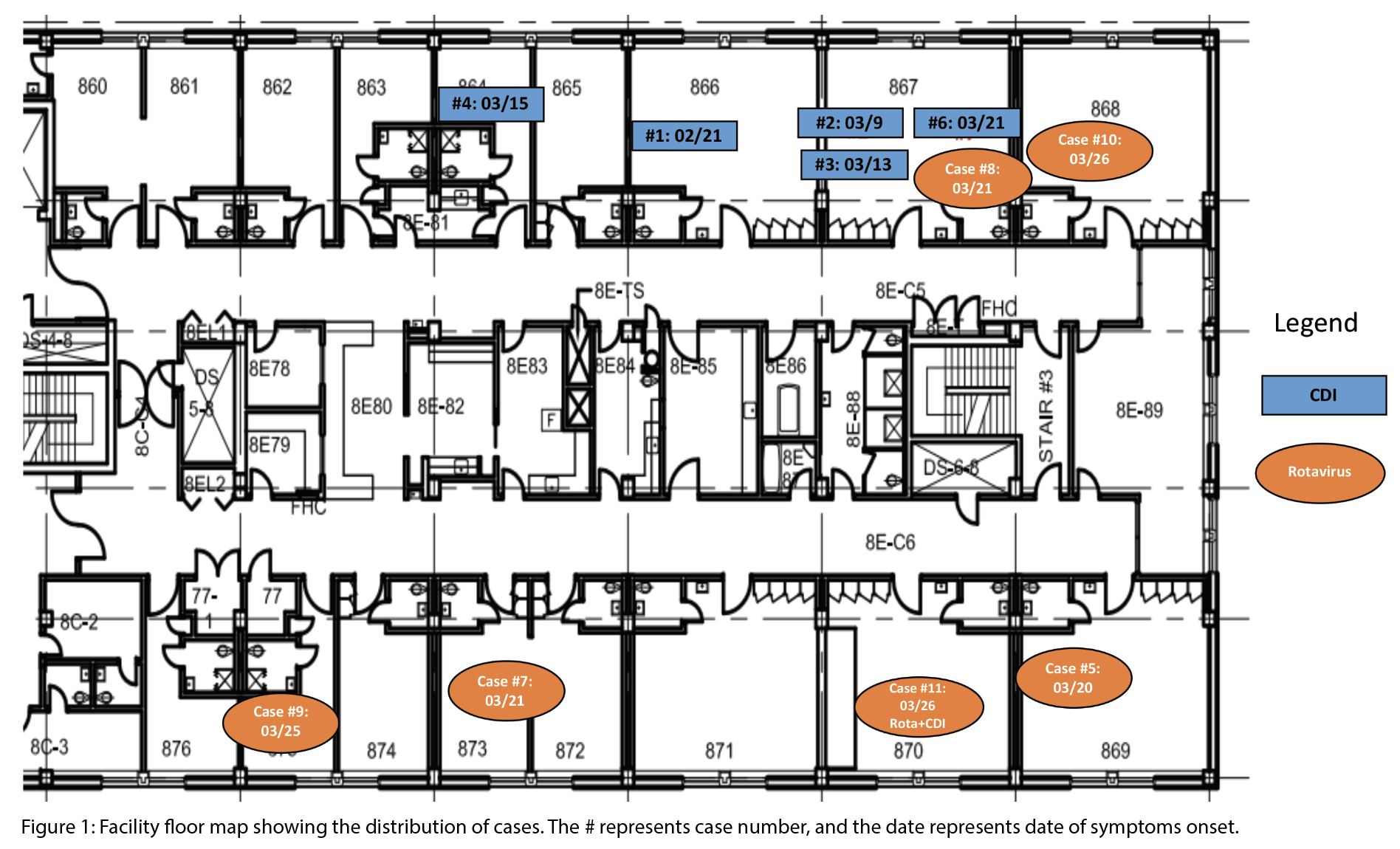

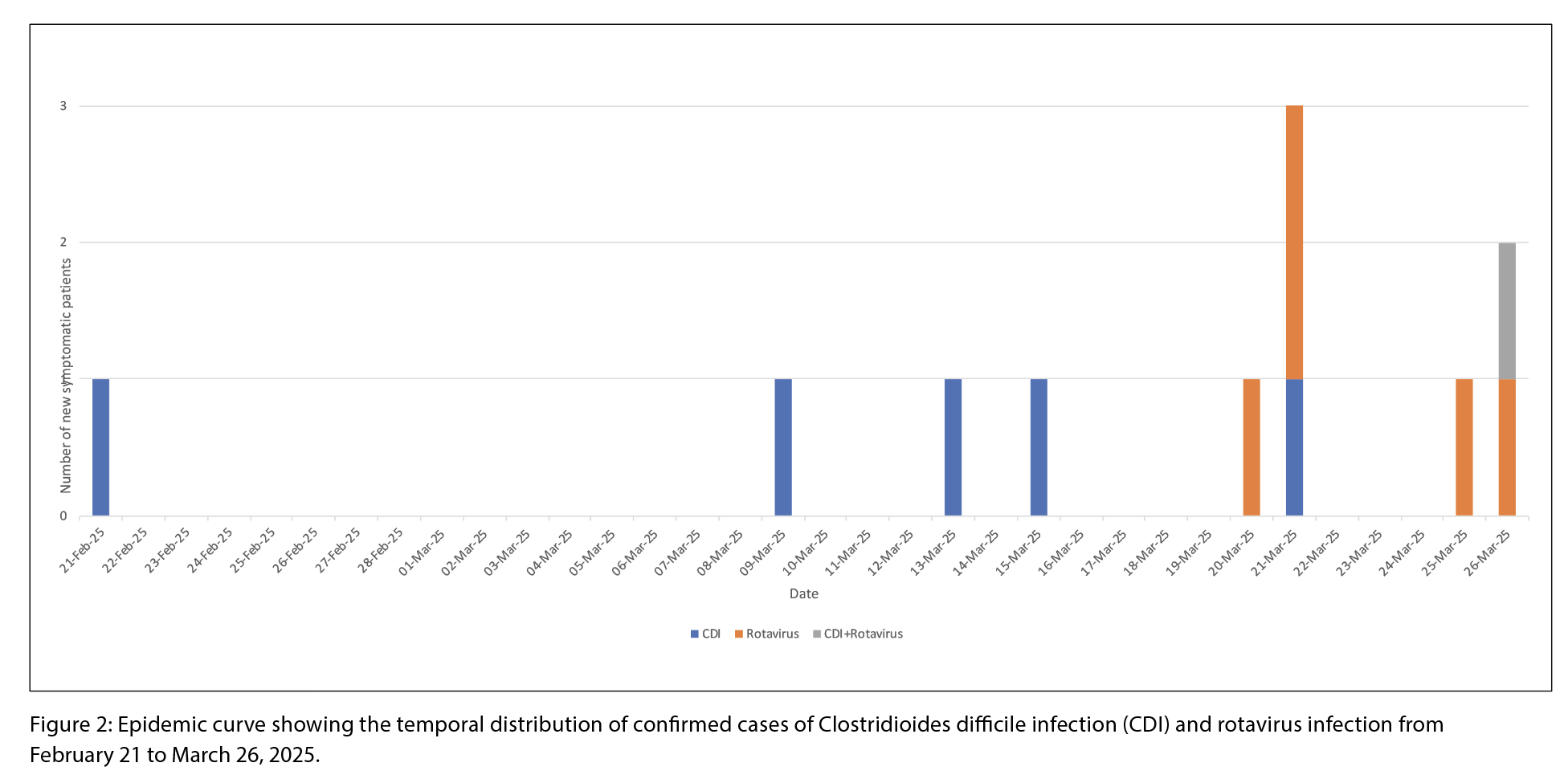

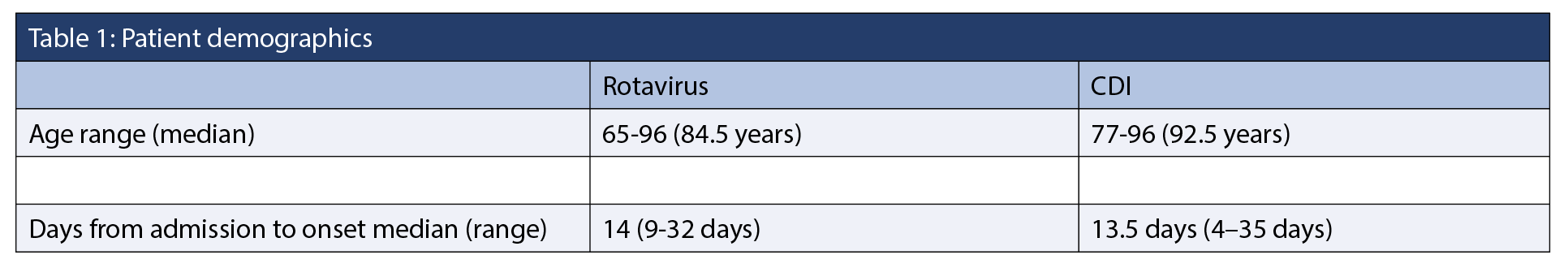

Between February 21 and April 10, 2025, five CDI cases and six rotavirus cases were identified, including one co-infection (Figure 1 and 2). During this period, 136 patients were admitted. The overall attack rates for rotavirus was 4.4%, and 3.7% for CDI. Female patients accounted for 50% of the rotavirus cases and 66.7% of the CDI cases (Table 1). Three CDI cases were epidemiologically linked to the same patient room (Figure 1). The earliest symptom onset date was February 21 in a patient with CDI. The rotavirus outbreak was declared over on April 2, and the CDI outbreak on April 10, about three weeks after control measures began. No patients experienced severe outcomes such as fulminant CDI, toxic megacolon, colectomy, or death. There were no reports of visits from ill children with gastroenteritis, or ill staff working on the ward or in the dietary department during this time. One case of co-infection of CDI and rotavirus was detected.

Environmental and hand hygiene audits

Environmental audits identified incomplete cleaning of patient rooms and shared equipment. UV light audits using fluorescent gel were used to identify areas that had not been properly cleaned. The gel was applied prior to cleaning and then inspected under a UV light afterward to determine whether it had been fully removed, partially removed, or missed. There were eight audits conducted on eight different days. Thirteen out of 15 rooms on the unit were audited. Audits revealed missed cleaning of several high-touch areas, including floor lift handles, glucometers, vital signs machines, mobile devices, and workstations on wheels. Following education provided by the environmental services supervisor, areas identified for improvement included toilet handrails and grab bars (previously missed four times), room doorknobs – specifically the inner doorknob (missed three times), and bathroom sinks (missed four times).

Staff compliance in hand hygiene was also suboptimal at 66.7% across 21 observed opportunities. Hand hygiene audits identified multiple areas for improvement, particularly Moment 2 (before an aseptic procedure), Moment 3 (after exposure or risk of exposure to blood or body fluids) and Moment 4 (after contact with a patient or patient’s environment). A facility audit identified barriers to handwashing, including water that was too cold.

In response, targeted education was delivered by managers, IPAC specialists, and clinical nurse educators (CNEs). Morning team huddles with the unit manager, along with just-in-time education provided by the IPAC team and CNEs, supported ongoing staff engagement. The IPAC team completed audits of the unit including staff hand hygiene compliance, use of personal protective equipment (PPE), cleaning wipes, and a visual inspection of the cleanliness of the unit. Charge nurses monitored compliance during IPAC off-shifts and weekends. Audit and feedback were repeatedly used to drive improvement throughout the outbreak period. Follow-up hand hygiene audits of 110 opportunities showed an increased compliance rate of 93.6%.

The environmental services supervisor reviewed the environmental audit results and provided 1:1 education to the staff member. Facility management repaired a handwashing sink to optimize water temperature. In addition, an audit found that staff were unsure where to dispose of commode waste. The waste was being disposed of in the biomedical waste stream, rather than the general waste container. Therefore, additional interventions included unit decluttering and reviews regarding human waste handling and commodes cleaning practices.

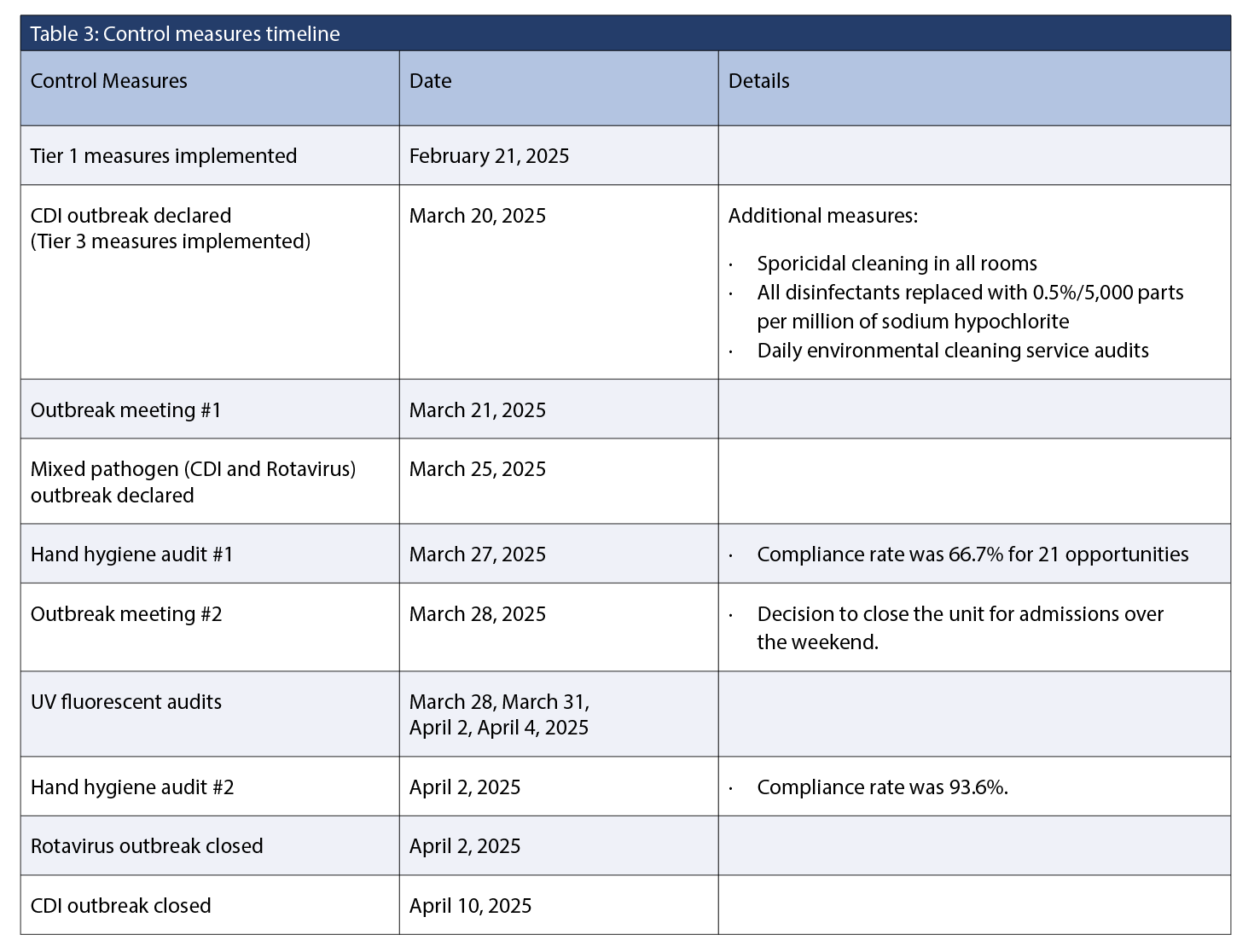

Control measures

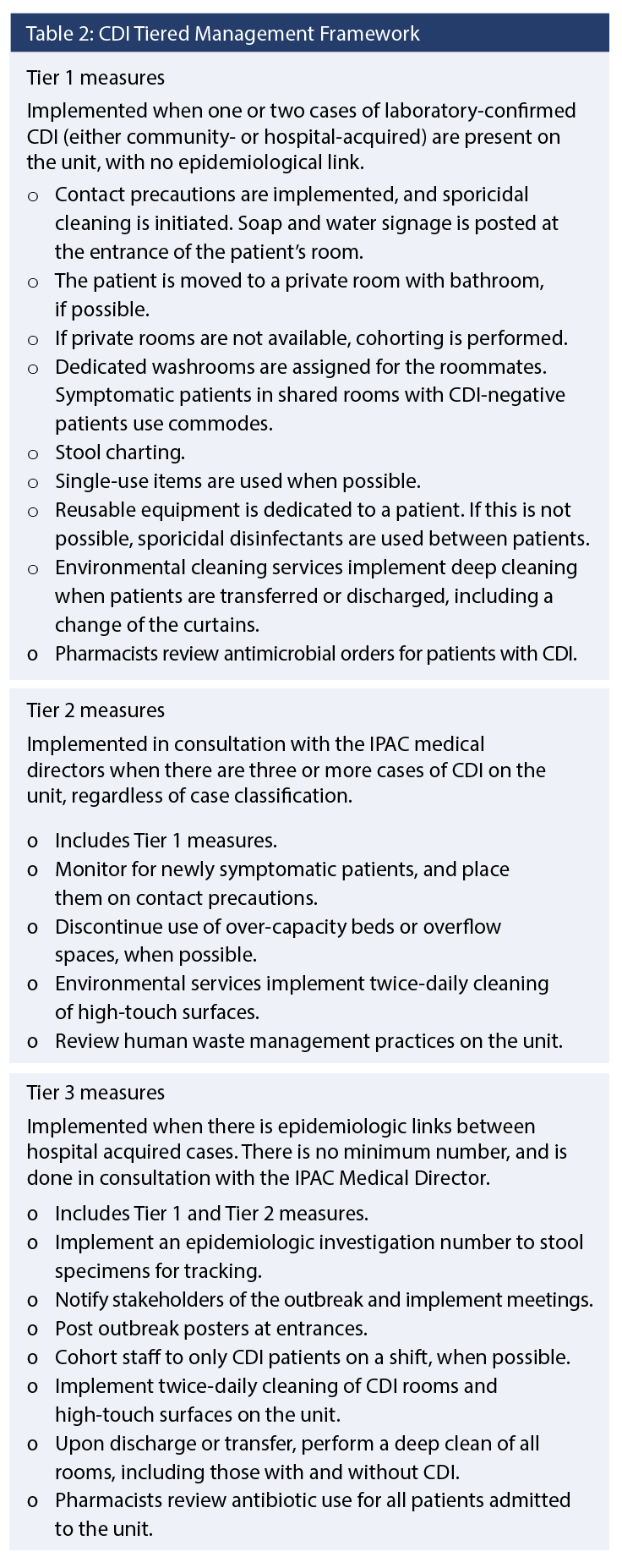

A tiered IPAC approach was implemented based on local CDI tiered management framework (Table 2 and Table 3). Tiered 1

measures were implemented upon identification of the first CDI case in February 2025. Following the detection of three or more epidemiologically linked, laboratory-confirmed CDI cases, an outbreak was declared, and Tier 3 measures were implemented. Tier 2 measures were bypassed due to the recognition of the epidemiologic links between cases. Because of the definitional criteria required to implement outbreak control measures, there was a delay in formally declaring the outbreak between the initial case in February and the subsequent cases in March. The environmental public health team was informed and provided with a line list of patients whenever new cases were reported during the outbreak, along with details of the control measures implemented. The Antimicrobial Stewardship Program (ASP) team was present in the hospital and reviewed the use of antimicrobials such as fluroquinolones, piperacillin-tazobactam, carbapenems, linezolid, and daptomycin. A communication was sent to ASP when the outbreak was declared.

Outbreak closure

The discontinuation criteria for lifting precautions were 48 hours without diarrhea and the passage of at least one formed stool. The outbreak was closed when all audits and control measures had been completed, and there was no evidence of ongoing transmission on the unit. However, one patient had both CDI and rotavirus towards the end of the outbreak. The rotavirus portion of the outbreak was closed seven days after the symptom onset date of the final rotavirus case. The IPAC team opted to double the incubation period due to its atypical presentation. The presentation was atypical for rotavirus, and outbreak definition was not initially met because cases were not identified within 48 hours of each other. The CDI outbreak was closed two weeks after the symptom onset date of the last case.

DISCUSSION

We describe a rare mixed-pathogen outbreak of CDI and rotavirus in a geriatric acute care unit. While rotavirus is well-recognized as a cause of paediatric gastroenteritis, its role in adult outbreaks remains underappreciated. This outbreak investigation highlights the importance of considering rotavirus as a potential contributor to gastroenteritis in older adults and hospitalized populations, especially during peak seasonal periods.

Impact of Infection Prevention and Control measures

Despite early implementation of Tier 1 contact precautions and sporicidal cleaning for the initial CDI case, transmission of both pathogens continued. This highlights the need for a rapidly escalating, tiered IPAC response to contain an outbreak. Key Tier 3 interventions and additional measures that contributed to outbreak control included:

Enhanced environmental cleaning: All disinfectants were replaced with 0.5% (5,000 ppm) sodium hypochlorite, a sporicidal agent effective against both pathogens. UV fluorescent audits revealed persistent deficiencies in high-touch surface cleaning and inappropriate waste disposal. Real-time audit feedback and targeted re-education of environmental services staff led to improved cleaning practices.

Hand hygiene interventions: Initial staff hand hygiene compliance was suboptimal (66.7%). Following targeted education and frequent auditing, compliance improved to 93.6%, demonstrating the effectiveness of continuous feedback and engagement.

Staff cohorting and education: Where feasible, staff were cohorted to CDI care. Training covered proper PPE use, soap-and-water handwashing for CDI, and cross-contamination risks. While toilet use is generally preferred during diarrheal outbreaks to minimize contamination risk, the hospital’s infrastructure required that patients with diarrheal illness in shared rooms utilize bedside commodes. This measure aimed to reduce the potential for cross-contamination associated with shared toilet facilities.

Closure of the unit and admission restrictions: Temporary closure enabled deep cleaning and limited additional exposure risks.

Stakeholder communication and coordination: Regular outbreak meetings enabled timely decision-making, coordinated responses, and protocol updates.

Collectively, these interventions demonstrate the effectiveness of a layered, multidisciplinary approach to outbreak management (Dubberke E 2012). Timely implementation of additional precautions, paired with environmental and behavioural interventions was essential to curbing pathogen transmission in this complex outbreak scenario.

An important approach in the management of this mixed-pathogen outbreak is replacing all disinfectants with 0.5% (5,000 ppm) sodium hypochlorite to effectively inactivate both organisms. It has previously been shown that, given the robust nature of C. difficile spores, standard hospital-grade disinfectants may not be effective, and agents that are sporicidal must be used, including sodium hypochlorite (at a concentration of least 0.5%) or hydrogen peroxide (A.N. Edwards et al., 2016; Pereira et al., 2015). Standard disinfectants such as isopropyl alcohol and quaternary ammonium compound wipes, which are commonly used in our hospital, are ineffective against C. difficile spores. Without clear guidance or label recognition, frontline staff may inadvertently assume these products are appropriate for use in outbreak settings. Sporicidal agents (e.g., ≥0.5% sodium hypochlorite or hydrogen peroxide formulations) are required for C. difficile decontamination. Meanwhile, rotavirus is susceptible to a broader array of disinfectants, including sodium hypochlorite (≥ 0.05%), glutaraldehyde (2%), iodinated disinfectants (>10,000 ppm iodine), quaternary ammonium-alcohol mixtures, acids, or phenolic-surfactant combinations (Pereira et al., 2015; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2018). Therefore, in mixed-pathogen outbreaks, replacing agents that may not be effective with one that is effective against both organisms should be considered.

Clinical relevance of rotavirus testing in adults

Although rotavirus is typically associated with paediatric illness, this outbreak highlights its significance in older adults. In this population, rotavirus infection may mimic C. difficile, with overlapping symptoms such as diarrhea and abdominal discomfort that can lead to misdiagnosis or missed cases. Accurate testing is essential, as treatment strategies differ significantly between the two infections.

Asymptomatic rotavirus shedding in adults may contribute to nosocomial transmission, posing significant risks to vulnerable populations. This silent transmission risk underscores the importance of considering rotavirus as a potential cause of gastroenteritis in adults, particularly during outbreaks or when other common pathogens have been ruled out. This can also have IPAC implications with regard to discontinuing additional precautions, particularly for immunocompromised individuals, as shedding may persist for extended periods of time (Anderson & Weber, 2004).

Vaccine-related considerations

There is currently no antiviral treatment or post-exposure prophylaxis for rotavirus. While effective paediatric vaccines are available, adult infections can still occur – particularly in older individuals who were not vaccine-eligible because the vaccine was introduced in Canada after 2011 and due to waning immunity (Muchaal et al., 2021; National Advisory Committee on Immunization, 2016). Paediatric vaccination programs offer indirect herd immunity benefits, and studies have shown significant reductions in adult rotavirus hospitalizations following widespread paediatric immunization (Anderson et al., 2013; Baker et al., 2019). However, the magnitude of protection declines with age, reinforcing the need for enhanced surveillance in high-risk adult populations (Anderson et al., 2013; Baker et al., 2019).

The key limitations of this study include its retrospective in design, small sample size, and the lack of molecular typing to confirm relatedness of isolates, although the epidemiological links and temporal clustering of cases support a common source of transmission. Testing was limited to patients with diarrheal symptoms; therefore, asymptomatic shedding and transmission may have occurred but could not be quantified, and its impact on the outbreak remains unknown. Moreover, no formalized patient hand hygiene program was established within the facility. Although patients were encouraged to perform hand hygiene following toileting and before meals, and had direct access to hand-wash sinks within their rooms, the absence of a structured and monitored program may have facilitated pathogen transmission. Because patient hand hygiene compliance was not formally audited, the extent of its impact on infection transmission remains indeterminate. Future initiatives could incorporate the development and evaluation of a standardized patient hand hygiene program to strengthen infection prevention and control practices. Only one co-infection was identified, limiting conclusions about the interaction between pathogens. Additionally, the possibility of a Hawthorne effect, in which heightened awareness during an audit may have temporarily improved infection control practices, limits the generalizability of observed behaviour (Chen LF et al., 2025).

CONCLUSION

To our knowledge, this is the first documented mixed CDI and rotavirus outbreak in a Canadian acute care setting among older adults. This underscores the importance of considering multiple pathogens in outbreak investigations and ensuring that surveillance and diagnostic practices are sufficiently broad. Viral testing is not routinely performed for all cases of diarrhea, particularly in adults, but should be considered during outbreaks when symptoms persist despite antibiotic treatment. This outbreak reinforces the importance of timely escalation of IPAC protocols and comprehensive diagnostic testing in managing multifactorial gastroenteritis outbreaks in healthcare settings.

REFERENCES

Alberta Health Services. (2024, December 3). Guide for outbreak prevention & control in acute care sites.

https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/webapps/labservices/indexAPL.asp?id=5100&details=true

Alberta Precision Laboratories | Lab Services. (2024,

January 12).

https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/webapps/labservices/indexAPL.asp?id=5100&details=true

Alberta Precision Laboratories | Lab Services. (2024, May 24).

https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/webapps/labservices/indexAPL.asp?id=9428&tests=&zoneid=

1&details=true

Anderson, E. J., Katz, B. Z., Polin, J. A., Reddy, S., Weinrobe, M. H., & Noskin, G. A. (2012). Rotavirus in adults requiring hospitalization. Journal of Infection, 64(1), 89–95.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2011.09.003

Anderson, E. J., Shippee, D. B., Weinrobe, M. H., Davila, M. D., Katz, B. Z., Reddy, S., … Noskin, G. A. (2013). Indirect protection of adults from rotavirus by pediatric rotavirus vaccination. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 56(6),

755–760. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cis1010

Anderson, E. J., & Weber, S. G. (2004). Rotavirus infection in adults. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 4(2), 91–99.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(04)00928-4

Baker, J. M., Tate, J. E., Steiner, C. A., Haber, M. J., Parashar, U. D., & Lopman, B. A. (2019). Longer-term direct and indirect effects of infant rotavirus vaccination across all ages in the United States in 2000–2013: Analysis of a large hospital discharge data set. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 68(6), 976–983. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciy580

Chen, L. F., Vander Weg, M. W., Hofmann, D. A., & Reisinger,

H. S. (2015). The Hawthorne effect in infection prevention and epidemiology. Infection Control & Hospital

Epidemiology, 36(12), 1444–1450.

https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2015.227

Choi, K. B., Suh, K. N., Muldoon, K. A., Roth, V. R., &

Forster, A. J. (2019). Hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infection: An institutional costing analysis. Journal of

Hospital Infection, 102(2), 141–147.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2019.01.019

Dubberke, E. (2012). Strategies for prevention of Clostridium difficile infection. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 7(3), S14–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1908

Edwards, A. N., Karim, S. T., Pascual, R. A., Jowhar, L. M., Anderson, S. E., & McBride, S. M. (2016). Chemical and

stress resistances of Clostridium difficile spores and vegetative cells. Frontiers in Microbiology, 7, 1698.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.01698

Edwards, N., Abasszade, J. H., Nan, K., Abrahams, T., La, P. B. D., & Tinson, A. J. (2023). Rotavirus gastroenteritis leading

to multi-organ failure in an adult. American Journal of

Case Reports, 24, e940967.

https://doi.org/10.12659/AJCR.940967

Finn, E., Andersson, F. L., & Madin-Warburton, M. (2021). Burden of Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI)–

A systematic review of the epidemiology of primary and recurrent CDI. BMC Infectious Diseases, 21, 456.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06147-y

Lee, R. M., Lessler, J., Lee, R. A., Rudolph, K. E., Reich, N. G.,

Perl, T. M., & Cummings, D. A. (2013). Incubation periods of viral gastroenteritis: A systematic review. BMC Infectious Diseases, 13, 446.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-13-446

Lourenço, L. C., Prosty, C., Huttner, A., Lee, T. C., & McDonald, E. G. (2025). Approach to Clostridioides difficile diarrheal infection. CMI Communications, 2(2), 105079.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmicom.2025.105079

Morton, V. K., Thomas, M. K., & McEwen, S. A. (2015). Estimated hospitalizations attributed to norovirus and rotavirus infection in Canada, 2006–2010. Epidemiology and Infection, 143(16), 3528–3537.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268815000734

Muchaal, P. K., Hurst, M., & Desai, S. (2021). The impact of publicly funded rotavirus immunization programs on Canadian children. Canada Communicable Disease Report, 47(2), 97–104. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v47i02a02

National Advisory Committee on Immunization. (2016, April).

Rotavirus vaccines: Canadian immunization guide.

https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/

reports-publications/canada-communicable-disease-report-ccdr/monthly-issue/2010-36/canada-communicable-disease-report-9.html

Pereira, S. S. P., Oliveira, H. M. D., Turrini, R. N. T., & Lacerda, R. A. (2015). Disinfection with sodium hypochlorite in hospital environmental surfaces in the reduction of contamination and infection prevention: A systematic review. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP, 49(4), 681–688.

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0080-623420150000400020

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2018, June 13). Pathogen safety data sheets: Infectious substances – Human rotavirus [Education and awareness; guidance].

https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/laboratory-biosafety-biosecurity/pathogen-safety-data-sheets-risk-assessment/human-rotavirus.html

Wenman, W. M., Hinde, D., Feltham, S., & Gurwith, M. (1979). Rotavirus infection in adults. New England Journal of Medicine, 301(6), 303–306.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM197908093010604

Xia, Y., Tunis, M., Frenette, C., Katz, K., Amaratunga, K., Rhodenizer Rose, S., House, A., & Quach, C. (2019). Epidemiology of Clostridioides difficile infection in Canada:

A six-year review to support vaccine decision-making.

Canada Communicable Disease Report, 45(7/8), 191–211.

https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v45i78a04