As members of the Ontario Infection Control Professionals Action Coalition (OICPAC), we write to highlight a critical gap in Ontario’s healthcare system, the absence of regulation for Infection Prevention and Control (IPAC) professionals. Despite playing an essential role in safeguarding patient safety and public health, IPAC professionals are not a recognized or self-regulated health profession in Ontario (or elsewhere in Canada). They lack title protection, entry-to-practice requirements, a regulatory body, and a legislative framework.

Heather L. Candon, MSc, MHM, CIC1*, Bois Marufov, MD, MSc, CIC1, Kelsey Houston, MPH, CIC1, Lorraine Maze dit Mieusement, RN, MN, CIC1, Murtuza Diwan, BSc (Hons), DLSHTM, MSc, CIC1, Maryam Salaripour, BSc, MPH, PhD1, Zahir Hirji, BScN, MHSc, RN, CIC1, Kevin J. Stinson, PhD, CIC, RMCCM1, and Lisa Mills, RN, BScN, CIC1

1 Ontario Infection Control Professionals Action Coalition (OICPAC), Ontario, Canada

*Corresponding author

Heather L. Candon

Sunnybrook

2075 Bayview Ave

Toronto, Ontario M4N 3M5

Canada

Article history:

Received 25 July 2025

Received in revised form 17 October 2025

Accepted 22 October 2025

As members of the Ontario Infection Control Professionals Action Coalition (OICPAC), we write to highlight a critical gap in Ontario’s healthcare system, the absence of regulation for Infection Prevention and Control (IPAC) professionals. Despite playing an essential role in safeguarding patient safety and public health, IPAC professionals are not a recognized or self-regulated health profession in Ontario (or elsewhere in Canada). They lack title protection, entry-to-practice requirements, a regulatory body, and a legislative framework.

IPAC professionals in Ontario come from diverse fields such as laboratory science, nursing, medicine, microbiology, public health, and more, including internationally trained healthcare professionals. While these backgrounds offer foundational knowledge, none provides the specialized formal training required for effective IPAC practice. Many pursue voluntary educational certificates such as those offered by IPAC Canada, and/or attempt certification exams through the U.S.-based Certification Board of Infection Control (CBIC). However, without regulation, entry-to-practice standards, accountability, and advocacy remain inconsistent, and public safety can be compromised. The need for a Canadian certification framework remains urgent but lies beyond the scope of this letter.

The SARS Commission Report in Ontario (Campbell, 2006) exposed major deficiencies in IPAC resources, education, and training. Almost two decades later, COVID-19 revealed persistent gaps, particularly in long-term care (LTC) settings where the consequences were devastating. While some healthcare facilities have improved resources, standardized IPAC training, defined scopes of practice, and mechanisms for accountability are still lacking.

Currently, IPAC skills are often acquired through on-the-job experience and non-standardized education. Yet IPAC professionals are expected to possess wide-ranging competencies – from microbiology, epidemiology, and statistics to outbreak management, occupational health and safety, leadership, quality improvement, and healthcare facility design (Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology [APIC], n.d.; Infection Prevention and Control [IPAC] Canada, 2022). These vital skills demand a robust and structured framework. Furthermore, inconsistent use of medical directives for IPAC professionals across institutions highlights the need for regulatory oversight. Failures in this area can lead to serious harm, legal repercussions, and public mistrust, as evidenced by Canadian class action lawsuits related to preventable outbreaks (Bailey & Ries, 2005; CBC News, 2008; Lang, 2024).

While Ontario’s Fixing Long-Term Care Act (Ontario Government, 2024a) mandates IPAC resources in LTC homes, it does not specify the educational requirements for entry to practice required. Similarly, neither the Public Hospitals Act (Ontario Government, 2024b), the Occupational Health and Safety Act (Ontario Government, 2025), nor their associated regulations specify required credentials for those leading IPAC programs or working as IPAC professionals.

Ontario has 26 regulatory colleges governing 29 health professions under the Regulated Health Professions Act (RHPA; Ontario Government, 2024c). Regulatory colleges ensure public safety by setting education and practice standards, monitoring professional conduct, and maintaining accountability. In contrast, professional associations such as IPAC Canada offer support and advocacy but do not regulate practice.

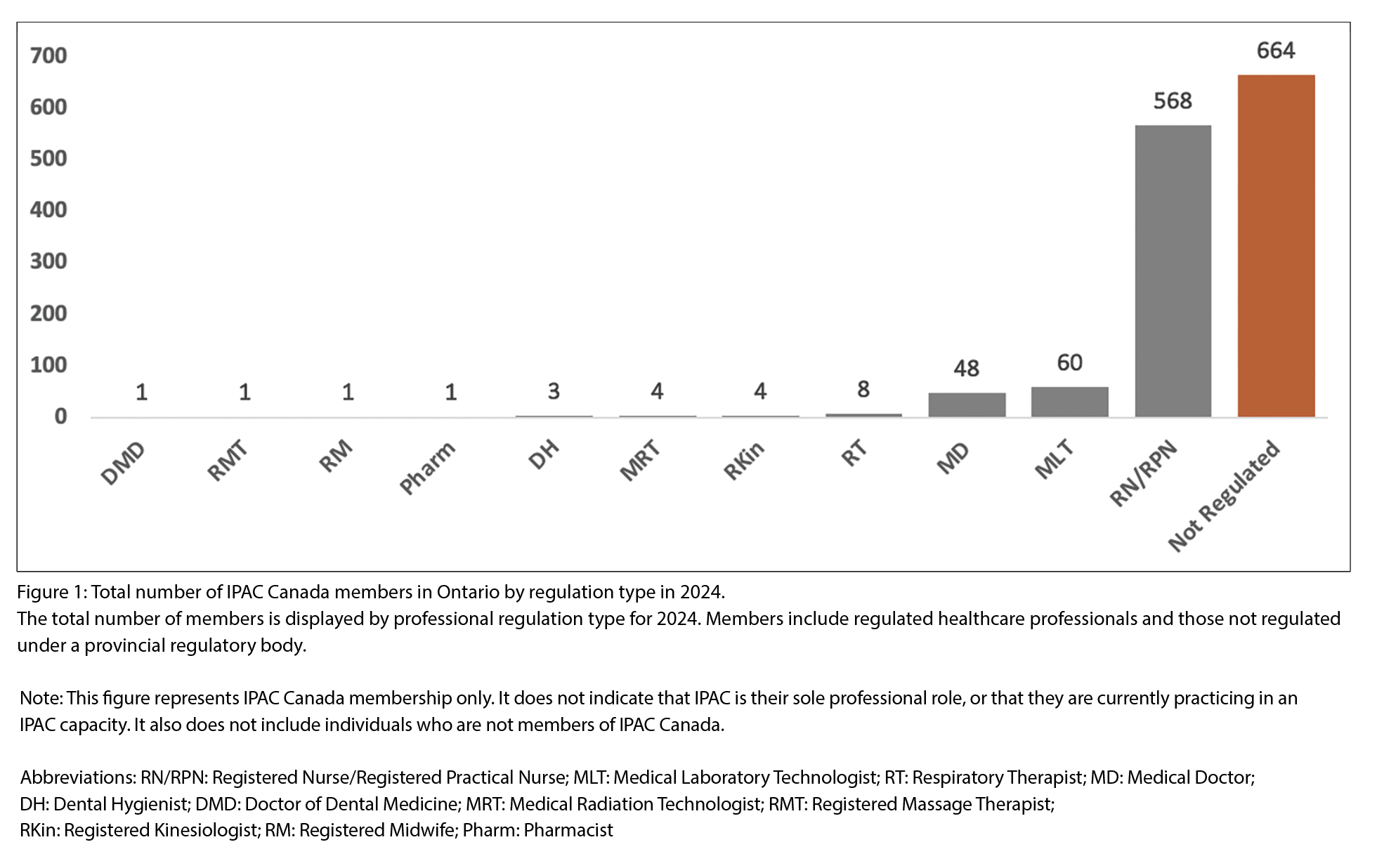

We estimate that more than 1,500 professionals in Ontario are fully or partially responsible for IPAC programs. According to 2024 IPAC Canada data, Ontario has 664 otherwise unregulated IPAC Canada members and 699 members who belong to a pre-existing regulatory college (Figure 1).

The degree of regulation varies by region. For instance, 40% of IPAC Canada members in the Greater Toronto Area are regulated through another college, while Ottawa has the highest proportion at 69%. Historically, the Health Professions Regulatory Advisory Council (HPRAC) advised the Ontario Minister of Health on whether a profession should be regulated. HPRAC has since been disbanded, leaving this responsibility to OICPAC to build the case for self-regulation of IPAC professionals. The area of focus includes strategic political advocacy, surveys (OICPAC, 2025b), stakeholder engagement, and preparation for drafting an application for regulatory status.

Benefits of Regulation

Standardization, accountability, and public safety

A regulatory college would set consistent qualification, practice, and ethical standards. This would ensure all IPAC professionals possess the knowledge, skills, and judgment required for safe and effective practice. Regulation introduces formal mechanisms for public accountability, quality improvement, and disciplinary action.

Enhanced professional recognition

Self-regulation would elevate the status of IPAC professionals within the healthcare system, enabling more effective advocacy for resources and integration in leadership. Title protection, clearly defined scopes of practice, and standardized credentials would strengthen the identity and visibility of the profession and improve recruitment and retention.

Preparedness and adaptability

A regulatory college would position the IPAC profession to be more agile in responding to emerging threats. Just as pharmacists have expanded their scope to meet changing healthcare needs, regulated IPAC professionals could adapt to new roles in outbreak management and contribute to healthcare system resilience.

Considerations for review and discussion

· Fees: Dual fees may apply if IPAC professionals are already members of another regulatory college, depending on the regulatory model adopted.

· Mobility: Regulation could improve interprovincial mobility if IPAC becomes recognized under national frameworks.

· Unionization: Regulation governs professional accountability based on designation, not workplace. Union representation may change with job classification, but regulation and union roles remain separate.

These are important considerations that OICPAC has heard through town halls, surveys, and direct feedback. We will be publishing a forthcoming piece that digs into this issue in depth, drawing directly from the survey feedback we have received to date. We remain committed to open dialogue and to exploring solutions as we continue on the long path toward seeking regulatory review in Ontario.

CONCLUSION

The need for regulation and self-governance of IPAC professionals in Ontario is both evident and urgent. As the field of infection prevention and control faces increasing complexity, emerging infectious threats, and ever-rising expectations, regulation will ensure that IPAC professionals are equipped, accountable, and empowered. We invite IPAC professionals across Ontario to complete our survey

by scanning the QR code (Figure 2) and help shape the future of our profession. The road ahead is challenging, but the safety of patients and the public – as well as the integrity and sustainability of our profession make this effort indispensable.

REFERENCES

Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology. (n.d.). Infection preventionist (IP)

competency model.

https://apic.org/professional-practice/infection-preventionist-ip-competency-model/

Bailey, T. M., & Ries, N. M. (2005). Legal issues in patient safety: The example of nosocomial infection. Healthcare Quarterly, 8(Special Issue), 140-145.

Campbell, A. (2006, December). Spring of fear: Volume 2.

The SARS Commission.

https://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/e_records/

sars/report/v2.html

CBC News. (2008, July 10). Families launch $50M proposed

class action after C. difficile outbreak.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/families-launch-50m-proposed-class-action-after-c-difficile-outbreak-1.769006

Infection Prevention and Control (IPAC) Canada. (2022, September). Core competencies for infection prevention

and control professionals (ICPs).

https://ipac-canada.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/IPAC_CoreCompetencies_ICPs_2022_revised-1-2.pdf

Lang, E. (2024, March 14). 6 Ontario LTC providers face class action lawsuits for alleged gross negligence during pandemic. CBC News.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/class-action-ltc-1.7143572

Ontario Government. (2024a, June 28). Fixing Long-Term Care Act, 2021, S.O. 2021, c. 39, Sched. 1.

https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/21f39

Ontario Government. (2024b, June 28). Public Hospitals Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. P.40.

https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/90p40

Ontario Government. (2024c, December 1). Regulated Health Professions Act, 1991, S.O. 1991, c. 18.

https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/91r18

Ontario Government. (2025, January 1). Occupational Health and Safety Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. O.1.

https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/90o01

Ontario Infection Control Professionals Action Coalition. (2025a). Infection prevention and control self-regulation. https://sites.google.com/view/oicpac

Ontario Infection Control Professionals Action Coalition. (2025b). Ontario Infection Control Professional application for regulation review under RHPA, 1991 survey.

https://docs.google.com/forms/d/1vd-48cO3swvavf3MLo3GNTfAeUJdfH0CRR3ybd4mKXM/viewform?pli=1&pli=1&edit_requested=true