Florence Yip, BSc FHN MHA(c)1*; Leah Diamond, RN, BSN, MSc PH(c)1

1Vancouver Coastal Health, British Columbia, Canada

*Corresponding author:

Florence Yip

Vancouver Coastal Health, B.C., Canada

email:florence.yip@vch.ca

ABSTRACT

The World Health Organization Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care provide an evidence-based framework to improve hand hygiene compliance through a multimodal approach which includes quality improvement, patient/resident engagement, and a commitment to safety. Long-term care (LTC) is considered both a resident’s home and a healthcare environment where healthcare workers provide professional care while balancing and honouring a homelike ambience. By engaging residents and their families (i.e., direct family members, friends, or caregivers) in four LTC homes through surveys and interviews, this quality improvement project aimed to understand the resident and family experience with hand hygiene measures in LTC, to learn how to promote both safety and comfort through their experiences, and to include what matters to them in the pursuit of this balance when developing hand hygiene programs.

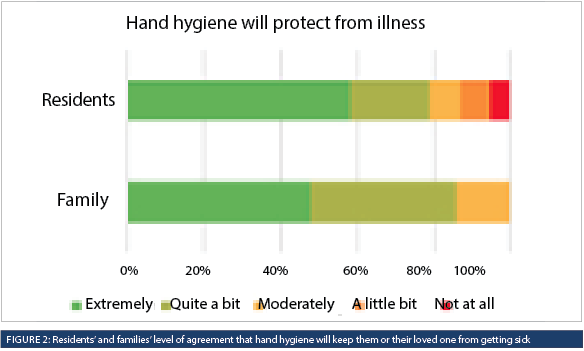

Using a mixed-methods approach, the findings suggest that residents and families support increased accessibility to hand hygiene infrastructure, including prioritizing access to soap and water; adding alcohol-based hand rub to resident rooms when appropriate; modelling good hand hygiene practices; and continuing hand hygiene reminders at entrances. More than 79% of residents and 85% of families felt that hand hygiene would help protect them or their loved one from getting sick. The opinions shared by residents and families were well-received, strengthened relationships between Infection Prevention and Control (IPAC) and facility staff, and provided a common understanding that improvements in hand hygiene accessibility are welcomed.

INTRODUCTION

The simple task of cleaning one’s hands at the right time and in the right way is considered the most effective intervention to decrease healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) in clinical environments (World Health Organization, 2009). The World Health Organization (WHO) Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in healthcare provide an evidence-based framework to improve hand hygiene compliance through a multimodal approach which includes quality improvement, a commitment to resident safety, education and training, observation and feedback, improvements in hand hygiene infrastructure, and visual reminders in the clinical space (World Health Organization, 2009). Hand hygiene infrastructure includes a dedicated and convenient location to access the necessary components to perform proper hand hygiene, including alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR), and sinks with soap and water. Although there has been a traditional emphasis on staff compliance with the five moments of hand hygiene, the WHO guidelines also emphasize patient/resident engagement and empowerment to improve self-care and safety. Resident inclusion in hand hygiene campaigns is critical in complex care environments like long-term care (LTC), where residents have direct contact with one another and their care environment through communal living activities (Strausbaugh, 2001; Utsumi et al., 2010).

LTC residents are particularly vulnerable and their voices are often not heard. This was amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic where the morbidity and mortality rates witnessed during outbreaks compromised the reputation and trust in the delivery of safe care between residents, families, staff, and stakeholders (Office of the Seniors Advocate, 2021). Provincial health orders mitigated the risk of transmission of COVID-19; however, strict visitation restrictions had the unintended consequences of social isolation and loneliness, highlighting the need to include resident and family voices in care delivery using a person-centred approach (Havaei, 2022).

To provide quality care in LTC, staff must traverse evidence-based practice, clinical norms, and resident preferences to achieve the most favourable balance of risks and benefits in a space considered the resident’s home (Coulter, 2007; Haenen, et al., 2022; Mountford & Shojania, 2012). Proposing multimodal hand hygiene programs in LTC during the pandemic has been met with some resistance where the acceptability and impact of these interventions on a resident’s care experience still need to be discovered. For example, there is a concern that installing wall-mounted ABHR at the point of care will leave the space feeling less homelike. This narrative is a common barrier when developing hand hygiene programs. Research indicates that LTC staff constantly strive to balance infection control, responding adequately to care needs, and maintaining a homelike environment for their residents (Haenen et al., 2022).

Respect for preferences and understanding what matters most to patients, residents, and families are key pillars of patient-centred care or person-centred care (Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2023; Picker Institute Europe, n.d.). Understanding and improving resident and family experiences are associated with improved health outcomes, quality of life, and communication with staff and providers (Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality, 2020). Person-centred care in LTC shifts the resident to the centre and supports their preferences and autonomy, which can enhance resident well-being and their emotional and social needs (Williams et al., 2015). Therefore, moving forward with a person-centred approach to hand hygiene can be seen as an opportunity to build trust and improve the delivery of care from the perspective of the resident.

There have been studies exploring the feasibility and effectiveness of resident hand hygiene interventions and the acceptability of specific products within LTC (Knighton et al., 2017; O’Donnell et al., 2015; Rai et al., 2017; Schweon et al., 2013). However, none have explored the acceptability or resident experience of implementing multimodal resident-focused hand hygiene programs in these settings. Therefore, this quality improvement project was initiated in collaboration between one health authority’s Infection Prevention and Control (IPAC) team and Experience in Care (EIC) team, whose purpose is to use a person-centred approach to understand, embed, and improve experience in care in partnership with residents, families, and healthcare workers. This aim of the project was also to understand resident and family experience with hand hygiene measures in LTC, to learn how to promote safety and comfort through their experiences, and to include what matters to them in pursuing this balance when developing hand hygiene programs.

METHODS

This quality improvement project focused on hand hygiene in four long-term care homes within a regional health authority.

The EIC team utilized a mixed methods approach to engage residents and families, including in-person interviews for residents and an online survey for families at four LTC homes across the health authority to understand their experiences with the hand hygiene measures in their LTC homes. The survey questions included demographic questions, Likert-scale response options, and open-ended questions (Appendix A and B). The questions for residents and families were developed to permit comparison, however, the resident interview questions were developed using plain language, and were presented with visual analogue boards developed and tested by the British Columbia Office of Patient-Centred Measurement (BC PCM, n.d.). These visual analogue boards were designed to lower the barrier to participation for respondents with visual, auditory and cognitive decline for the surveys commissioned by the Office of the Seniors Advocate of British Columbia for the 2016/17 and 2022/23 cycles of provincially coordinated surveys of almost 30,000 residents and their frequent visitors in all publicly funded beds in 297 homes across British Columbia (BC PCM, n.d.; Office of the Seniors Advocate, 2017; Office of the Seniors Advocate, 2022.).

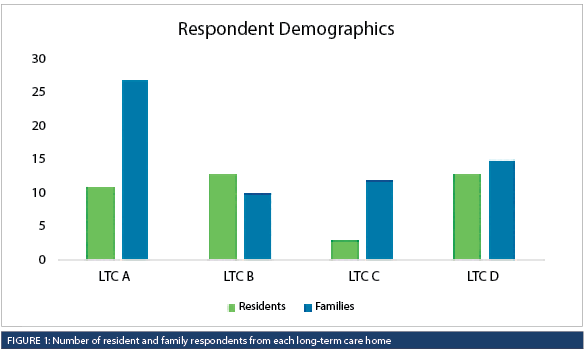

The residents were invited to complete a voluntary interview with one member of the EIC team, who was not involved in the resident’s care, as a way to reduce bias and increase neutrality, confidentiality, and the psychological safety of respondents. The EIC member paraphrased and transcribed the residents’ answers from the open-ended questions. Infection Control Practitioners (ICPs) were not involved with conducting interviews to further reduce bias. All of the questions were optional, and respondents were given the opportunity to end the interview at any time. A convenience sample of 40 residents at four LTC homes consisting of 11, 13, 3, and 13 residents were interviewed at each home (Figure 1). The one-on-one interviews were completed between November 2021 to March 2022 with a pause from December 2021 to January 2022 due to priorities related to the COVID-19 response. The EIC team also partnered with volunteers to offer interviews conducted in languages requested by the residents, including Mandarin and Cantonese, at one LTC home.

A voluntary online survey using a secure survey platform-Checkbox, was distributed through the LTC administrator’s contact lists to the resident’s chosen family (i.e., family member, friend, or caregiver) and invitation posters were also designed and posted throughout the facilities to promote the online survey and invite families to participate. In total, 64 survey responses from families were collected between November 2021 and December 2021, and all responses were anonymous and confidential. Participants who chose not to respond to particular questions were not included in the denominator data for that question.

The quantitative responses were analyzed in Microsoft Excel by one EIC member, and thematic analysis was used to identify and group the comments from the open-ended questions into themes and reviewed by another member of the EIC team. Blinded and independent data verification was not completed for this quality improvement project.

Ethical considerations

This project was not submitted for research ethics board (REB) approval as the activities described here are outside of the scope of ethics board review as per the Tri-Council Policy Statement 2 (2018), Article 2.5: “Quality assurance and quality improvement studies, program evaluation activities, and performance reviews, or testing within normal educational requirements when used exclusively for assessment, management or improvement purposes, do not constitute research for the purposes of this Policy, and do not fall within the scope of REB review”.

RESULTS

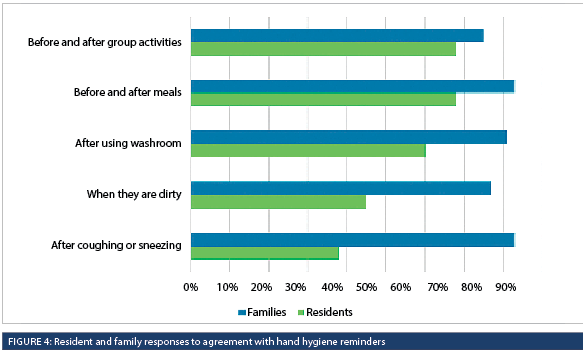

Overall, the survey and interview results showed strong support for hand hygiene with 79% (30/38) of residents and 86% (54/63) of families agreeing that hand hygiene would help protect them or their loved one from getting sick (Figure 2). Families highly valued reminders to wash their hands before and after meals, with a family member sharing, “My loved one has dementia and never remembers to use sanitizer, but the facility is very good with reminding him.” Residents also valued these reminders, but some shared that the reminders are not needed because hand washing should be common sense. One said, “I know to clean my hands after coughing or sneezing, and don’t need the reminder. Cleaning my hands when they are dirty is second nature.” Another resident said, “Washing hands when they are dirty or after coughing or sneezing should be automatic and common sense.”

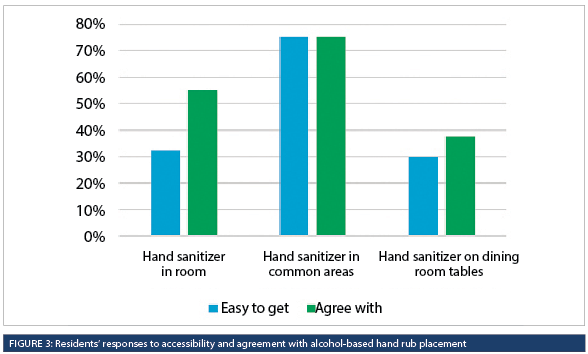

With respect to placement, 55% (22/40) of residents were supportive of having ABHR in their rooms, while 75% (30/40) of residents were supportive of having ABHR in common areas (Figure 3). However, in the open-ended questions, residents shared a strong preference for soap and water over ABHR, but also highlighted challenges accessing a sink. A resident shared, “I need assistance to move to the sink. I don’t like hand sanitizer, and don’t want to use hand sanitizer before meals. I prefer soap and water.” Another said, “It is difficult to reach the sink with soap and water. It is difficult to balance while washing hands. It is difficult to reach the hand sanitizer. I want to be able to wash my hands right before eating.”

When asked if they needed help to clean their hands, 45% (18/40) of residents reported needing help from staff or volunteers, and expressed gratitude for their assistance. One resident shared, “I’m really lucky to have a good group of staff helping me when I can’t wash my hands.” Another noted, “I like it when staff bring around hand sanitizer before meals.” Another resident expressed, “I want to clean my hands right away, but I need to wait for staff to help me,” and greatly appreciated staff who would help them, especially after meals.

In the open-ended questions, residents also reported, “Hand washing should be after everything we do. I ask staff if their hands are clean before handling my food. They say yes, but I don’t see them washing their hands. Rather than saying ‘Yes’, they should show me.” Another resident shared, “Watching staff clean hands is a good example for residents to learn.”

Overall, 77% (27/35) of residents and 79% (49/62) of families felt that their LTC home was doing a good job with hand hygiene. They shared sincere gratitude for and were impressed by the dedication of the staff working in their LTC home. Residents and families also felt that it was important to note the amazing work of all the staff in their home, which contributed to their positive experience. A resident shared, “Staff are marvelous, kind and understanding.” Another family member commented, “The staff are really wonderful in spirit and really care about the residents.”

DISCUSSION

Residents living in LTC are particularly vulnerable, and their voices and experiences are often not heard. This initiative aimed to understand the resident and family experience in LTC with the current hand hygiene measures, to understand which measures residents and families value most, and to learn how to promote safety and comfort by learning from their experiences. Through thoughtful engagement and one-on-one interviews with residents, the EIC team listened to stories that the residents shared as they responded to structured interview questions. Their stories highlighted their needs, values, and preferences around their homes’ current hand hygiene measures.

Through thematic analysis of the data, five recommendations were identified by the IPAC and EIC teams to address what matters to residents and families:

• Maintain an approach to hand hygiene in LTC that centres on the resident and family;

• Support and assist residents with hand hygiene before meals;

• Continue modelling good hand hygiene in front of residents;

• Continue hand hygiene reminders at entrances;

• Support improvements in hand hygiene infrastructure.

The findings from this project suggest that residents and families support improvements in hand hygiene infrastructure, including prioritizing access to soap and water; adding ABHR to resident rooms when appropriate; modelling good hand hygiene practices; and continuing hand hygiene reminders at entrances. The specific reasons residents prefer soap and water to ABHR were not explored; however, one resident expressed an aversion to the product prior to meals suggesting a possible negative association with taste or residual ABHR remaining on their hands. To improve compliance, it is worth investigating resident preferences in future quality improvement projects, including alternative products such as hand wipes, which may reflect more familiar hand hygiene practices.

The stories shared by residents and families were well-received and strengthened relationships between IPAC and facility staff wanting to develop multimodal hand hygiene programs which support best practices for staff to safely deliver care and integrate the preferences of residents and their families. Understanding the impacts of hand hygiene reminders and infrastructure specific to the needs of the people receiving care and the people delivering care supports the development of effective hand hygiene strategies based on the needs, preferences, and values of the specific population they intend to reach.

The belief that hand hygiene infrastructure cannot coexist within a homelike atmosphere is worth investigating with residents, particularly where it impedes placement in existing facilities, the design and planning of new ones, or the ability for staff to deliver safe care with clean hands. Clinical items, including ceiling lifts, raised toilet seats, call bells, and walkers, are placed in LTC without hesitation because they are tools

for delivering safe care and enhancing the quality of a resident’s life.

Adherence to evidence-based process measures such as hand hygiene compliance to prevent HAIs can feel distant and fail to capture the imagination and motivation of residents, visitors, and staff. Improving quality of care, in line with the Quadruple Aim of improving client experience, provider experience, population health, and reducing costs (Bodenheimer & Sinsky, 2014), demands clinicians to expand measures such as hand hygiene compliance and include additional measures directly relevant to those receiving and providing care, including their experience, satisfaction, and preferences (Mountford & Shojania, 2012). One of the unexpected findings from this project was the value residents placed on learning from staff modelling hand hygiene behaviour. Linking hand hygiene to a positive resident experience may be an effective motivator for staff when paired with HAI rates which they may or may not relate to their daily practice (Mountford & Shojania, 2012).

Limitations of this quality improvement project includes the distribution of the online survey for families, which was only available in English, and the in-person interviews, which were conducted primarily in English, with cognitively intact residents, and only in urban settings. This project was also conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have influenced the residents’ and families’ perceptions of hand hygiene programs and infrastructure.

The findings from this project facilitated ICPs to open up the conversation around hand hygiene programs and garner support for LTC providers to enhance infrastructure to meet IPAC standards and recommendations. Each LTC home is unique, and continued development of hand hygiene programs and infrastructure placement initiatives should include engagement with residents and their families to understand and improve their care experience.

REFERENCES

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). (2020). Section 2: Why Improve Patient Experience? Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/quality-improvement/improvement-guide/2-why-improve/index.html

BC PCM. (n.d.). Tools and Resources. https://www.bcpcm.ca/tools-and-resources

Bodenheimer, T., & Sinsky, C. (2014). From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Annals of Family Medicine, 12(6), 573–576. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1713

Coulter, A., & Ellins, J. (2007). Effectiveness of strategies for informing, educating, and involving patients. British Medical Journal, 335,24. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39246.581169.80

Freepik from Flaticon. (2023). Dinner [Image]. Flaticon. https://www.flaticon.com/free-icon/dinner_3567197

Freepik from Flaticon. (2023). Table Etiquette [Image]. Flaticon.https://www.flaticon.com/free-icon/table-etiquette_4223218

Government of Canada. (2018). Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans – TCPS 2. https://ethics.gc.ca/eng/policy-politique_tcps2-eptc2_2018.html

Haenen, A., de Greeff, S., Voss, A., Liefers, J., Hulscher, M., & Huis, A. (2022). Hand hygiene compliance and its drivers in long-term care facilities; observations and a survey. Antimicrobial Resistance andInfection Control, 11(1), 50.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-022-01088-w

Havaei, N. (2022). Learnings from the pandemic to rebuild long term care. https://bccare.ca/wp-content/uploads/

2022/06/MSFHR_Final-Report_FH_June-16-2022.pdf Institute for Healthcare Improvement. (2023). The Power of Four Words: “What Matters to You?” https://www.ihi.org/Topics/WhatMatters/Pages/default.aspx

Knighton, S. C., McDowell, C., Rai, H., Higgins, P., Burant, C., & Donskey, C. J. (2017). Feasibility: An important but neglected issue in patient hand hygiene. American Journal of Infection Control, 45(6), 626–629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2016.12.023

Mountford, J., & Shojania, K.G. (2012). Refocusing quality measurement to best support quality improvement: local ownership of quality measurement by clinicians. British Medical Journal Quality & Safety, 21(6), 519-23.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000859

O’Donnell, M., Harris, T., Horn, T., Midamba, B., Primes, V., Sullivan, N., Shuler, R., Zabarsky, T. F., Deshpande, A., Sunkesula, V. C., Kundrapu, S., & Donskey, C. J. (2015). Sustained increase in resident meal time hand hygiene through an interdisciplinary intervention engaging long-term care facility residents and staff. American Journal of Infection Control, 43(2), 162–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2014.10.018

Office of the Seniors Advocate. (2021). Review of COVID-19 Outbreak in Care Homes in British Columbia. https://www.seniorsadvocatebc.ca/osa-reports/covid-outbreak-review-report/.

Office of the Seniors Advocate. (2017). Every Voice Counts: Office of the Seniors Advocate Residential Care Survey Provincial Results. https://www.seniorsadvocatebc.ca/app/uploads/sites/4/2017/09/Provincial-Results-Final-HQ.pdf

Office of the Seniors Advocate. (2022). Volunteer Surveyor Training Manual: BC Office of the Seniors Advocate’s Long-Term Care Resident and Family Survey 2022-23. https://surveybcseniors.org/assets/media/Vol-SurveyorTraining-Manual-v4almostFinal-JKAug22.pdf

Picker Institute Europe. (n.d). The Picker Principles of Person-Centered Care. N.D. https://picker.org/who-we-are/the-picker-principles-of-person-centred-care/

Rai, H., Knighton, S., Zabarsky, T, F., Donskey, C, J. (2017). Comparison of ethanol hand sanitizer versus moist towelette packets for mealtime patient hand hygiene. American Journal of Infection Control, 45(9): 1033-1034.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2017.03.018

Schweon, S. J., Edmonds, S. L., Kirk, J., Rowland, D. Y., & Acosta, C. (2013). Effectiveness of a comprehensive hand hygiene program for reduction of infection rates in a long-term care facility. American Journal of Infection Control, 41(1), 39–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2012.02.010

SC Johnson Professional USA, Inc. (2023). Alcohol Hand Rub Dispenser [Image].. SC Johnson Professional USA, Inc. https://www.scjp.com/en-ca/products/alcohol-handrub-dispenser

SC Johnson Professional USA, Inc. (2023). Point-of-Care Dispensers [Image]. SC Johnson Professional USA, Inc. https://www.scjp.com/en-ca/products/point-care-dispensers

Smashicons from Flaticon. (2023). Basin [Image]. Flaticon. https://www.flaticon.com/free-icon/basin_2373569

Smashicons from Flaticon. (2023). Toilet [Image]. Flaticon. https://www.flaticon.com/free-icon/toilet_3130213

Strausbaugh, L. J. (2001). Emerging healthcare-associated infections in the geriatric population. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 7(2),268-271. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid0702.010224

Utsumi, M., Makimoto, K., Quroshi, N., & Ashida, N. (2010). Types of infectious outbreaks and their impact in elderly care facilities: a review of the literature. Age Ageing, 39(3), 299-305. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afq029

Williams, J., Hadjistavropoulos, T., Ghandehari, O., Yao, X., & Lix, L. (2015). An evaluation of a person-centred care programme for long-term care facilities. Ageing & Society, 35(3), 457-488. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X13000743

World Health Organization (2009). WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in healthcare. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241597906